We Borrow Everything

The tragic Tao of Jim Irsay... the NFL's resident gypsy billionaire who bought Jack Kerouac's scroll and Jerry Garcia's guitar just to set them free.

I’ve been thinking a lot about artifacts lately. The debris we leave behind, and how little it really matters in the end, just ends up someone else’s souvenir, at best.

I recently wrote on BroBible about Hunter S. Thompson’s 1972 dirt bike hitting the block on Bring a Trailer. It hammered for $37,250. That’s a lot of scratch for a vintage Husqvarna that’s been restored but won’t actually fire up. The buyer likely ignored the bike’s unique mechanical suspension for the provenance: a physical receipt from 1972, the year Random House published Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in hardcover, cementing the savage journey that had bled out in the pages of Rolling Stone just months prior. Hunter likely purchased that bike with the fresh checks that followed, a tangible souvenir from his opus about the death of the American Dream.

We, the collectors, buy these things because artifacts define us. They are the physical bookmarks in the chapters of our lives. When it comes to our heroes, we want to hold the proof that the magic actually happened.

If you don’t follow the NFL or the high-stakes world of rock memorabilia, you might not know Jim Irsay. To the sports world, he was the renegade owner of the Indianapolis Colts, an eccentric billionaire who inherited the team from his Midwest HVAC magnate father, Robert. It was Robert who orchestrated one of the most controversial moves in sports history, sneaking the franchise out of Baltimore in the dead of night aboard a fleet of Mayflower trucks in 1984.

Jim took that complicated inheritance and turned it into a Super Bowl powerhouse. He defied the typical buttoned-up suit archetype. He was the guy wearing aviators indoors, tweeting cryptic lyrics at 3 a.m., and treating the incredibly privileged path he was born into as a backstage pass to history. He spent decades assembling the “Jim Irsay Collection,” a traveling museum that held the holy grails of American pop culture. The inventory list is a smash-and-grab of the 20th century’s most iconic ghosts: Muhammad Ali’s shoes and the robe he wore to fight Frazier, Kurt Cobain’s Smells Like Teen Spirit guitar, Ringo Starr’s drum kit from The Ed Sullivan Show, and Hunter S. Thompson’s “Great Red Shark” convertible from his “savage journey into the heart of the American Dream.” His obsession with preserving the cool far outweighed his interest in mere wealth.

Jim had been a blip on my radar since 2002. That was the year he dropped $2.43 million on Jack Kerouac’s original On the Road scroll, snatching the holy scripture of the Beat Generation away from museums and private hoarders alike. I was in high school at the time, a cursory football fan mostly because of the Donovan McNabb-era Eagles, and I had just finished On the Road myself. It sent me down a major adolescent Kerouac rabbit hole, devouring Dharma Bums, Big Sur, and Desolation Angels in one frantic summer binge. I remember reading the headline about an NFL owner buying the scroll on ESPN.com’s Page 2 and thinking, Who is this guy? NFL owners usually buy superyachts and oil-obsessed senators, not 120-foot rolls of teletype paper taped together by a wine-drunk scribe who did laps around the country in Neal Cassady’s Cadillac.

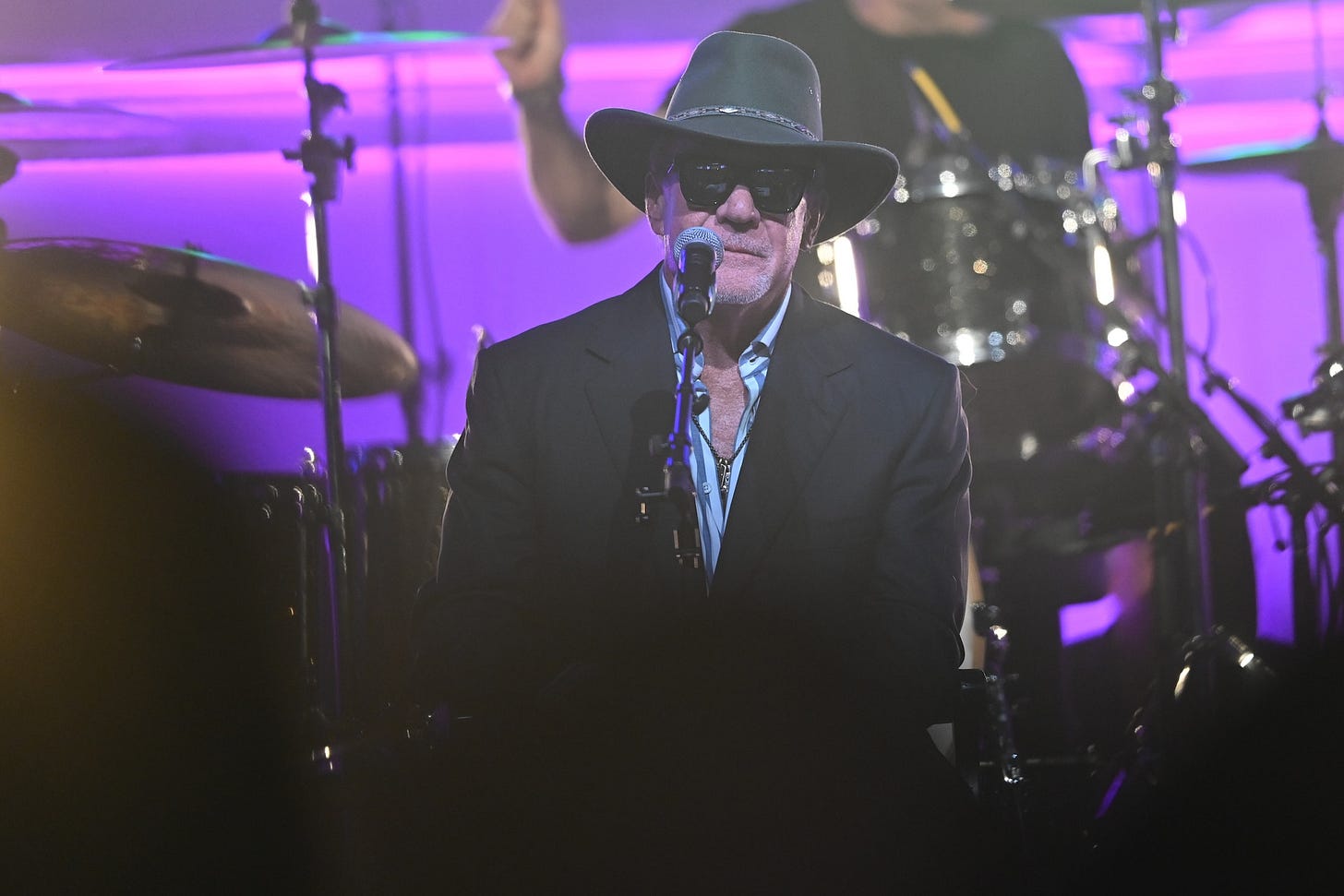

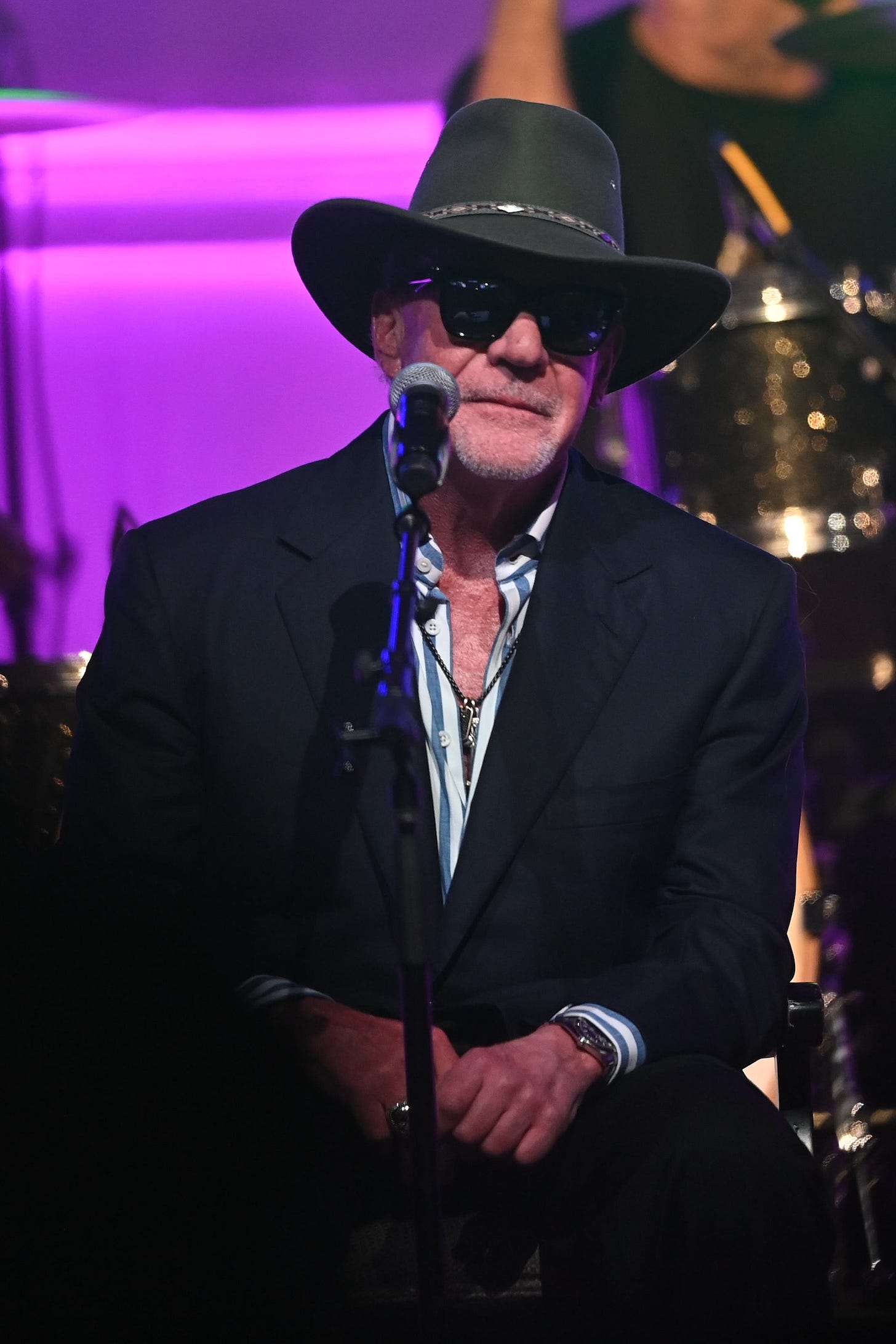

To me, Irsay was a Technicolor inkblot on the league’s white-tablecloth shield. He had decorum, but he was weird. He was my kind of weird. In a league of capitalist titans, that weirdness made him an absolute legend. He decided that the only way to honor these artifacts was to set them free. He didn’t lock them in a vault; he took them on tour. He threw massive, free parties in cities across America, inviting legends like Buddy Guy, Steven Stills, and John Fogerty to play with his house band, anchored by Kenny Wayne Shepherd, Mike Mills (R.E.M.), and Kenny Aronoff, while regular people walked past the holy relics he’d liberated with his football fortune.

Within the Colts organization, he was always “Mr. Irsay,” a title spoken with a brand of old-school weight and reverence usually reserved for titans of a different era. I only had forty minutes with him, but I quickly realized that the formality prioritized the serious responsibility he felt as the keeper of these legends over his billions. That responsibility became a part of his mythos. He was a magnificent steward in a world of historical hoarders, a total outlier to the rigid narrative machinery of the press box. That system is built for talk of salary caps, draft picks, and quarterback situations. No one ever thought to ask him who he was reading in high school, or which Grateful Dead show truly melted his face off.

And that’s what I wanted to do: ask him who he was reading in high school, or which Grateful Dead show melted his face off.

So when the “Jim Irsay Collection” tour announced a stop at San Francisco’s legendary Bill Graham Civic Auditorium in December 2022, I knew I had to get in the room. I’d already blown my chance to see the traveling circus in LA a year prior, and I was determined not to let the bus leave the station without me this time. Landing a one-on-one with an NFL owner is usually about as easy as getting a papal audience, especially when writing for an outlet called BroBible, but I saw a media inquiry email on the press release and shot a Hail Mary to Steve Campbell, the Colts’ VP of Communications.

I ditched the standard media playbook for an interview request, ignoring the lame arithmetic about reach, audience, and visits. Instead, I pitched him on my similar fascination with cultural giants and ghosts, many of whom were featured prominently in his collection. I told Campbell that before I was a publisher, I was a research assistant to Anita Thompson, helping her compile Ancient Gonzo Wisdom. I sent him a story I’d written about the time Anita returned a pair of elk antlers Hunter had brazenly stolen from Ernest Hemingway’s cabin, an extremely specific piece of literary history that I knew would resonate with a man like Jim. I acknowledged that pitching a literary retrospective for a site called BroBible was “left of center,” but I insisted that the real story lay in the wild, beautiful friendship between Jim and Hunter, rather than the artifacts themselves.

I didn’t ask to talk about football. I asked to talk about stuff like the Kerouac scroll.

Getting those 40 minutes with Jim became one of the great professional honors of my career. I published an article about it on BroBible shortly afterwards, pulling an all-nighter to make sure it was perfect before I flew up to SFO for the showing and concert that Saturday night.

Our call was on a Tuesday in early December 2022. I was at my desk in Los Angeles. Jim was on the other end of the Zoom, sitting in a grand, well-lit room that looked like a chapel at Elvis’s Graceland. He wore sunglasses indoors, sunk deep into a massive chair, chain-smoking cigarettes with a defiant cool. The vibes were heavy. The night before, his Colts had been thrashed by the Cowboys 54-19 on Monday Night Football, officially eliminating them from playoff contention. His handlers had been explicit before we connected: No football talk.

“So,” Jim asked, his voice crackling with a mischievous, gravelly energy, “are you centric more to Frisco, or all just the nation?”

Frisco. No one has called San Francisco “Frisco” since 1978. But Jim Irsay lived in a timeline where the Beats were still typing, the Dead were still touring, and the “unvarnished truth” was the only currency that mattered. Most NFL owners speak in carefully laundered PR-speak. They are the Prom Queens of capitalism. Mr. Irsay was the guy lighting fireworks in the back of the class.

“Are you ready?” he asked me five minutes into the call. “I’m ready to get loose for this question. Focus. As a journalist, tell me five things about yourself, one of them which isn’t true.”

He explained it as a screening method the CIA uses to identify high-level prospects, a way to see how a person pivots into fiction under pressure. He meant every word. I was completely flat-footed. I pride myself on being a pretty good conversationalist, but in these situations, I’m usually the one asking the questions, not the one being evaluated for agency potential. He prompted me with a hint: “Choice of favorite whiskey.” My brain short-circuited under pressure. For some reason, I blurted out Bacardi rum, a dimwitted reflex to being put on the spot by a man who owned the teletype scroll of the Beat Generation.

I rattled off a list of five: I’d been to a Super Bowl, an F1 race, a World Series. I mentioned the Bacardi. And I claimed I had seen Jerry Garcia live. Jim studied me like a scout watching tape on a defensive end. “I’m gonna say that you’re not such a big fan of Bacardi rum,” he finally declared.

He was wrong. The lie was Jerry Garcia. Jim had overestimated my age, figuring I was just old enough to have caught the Dead before Jerry passed in ‘95. “Maybe he is 43,” he reasoned aloud to me. I had to break it to him that I was only 37. I was just a kid in Pennsylvania when the trip ended. He laughed, a gravelly, genuine sound. “You had me go in there. Pretty good.”

I told him I’d grown up in Chambersburg, just down the road from his old prep school campus at Mercersburg Academy. “No way,” he said, the curiosity cutting through the smoke. I mentioned my own book-writing dreams. It was a scrap of shared geography and shared hunger, a tiny artifact bridging the gap between a kid from Central PA and the man who held the teletype scroll. At this point, after getting comfortable with each other, we were locked in.

Jim passed away in May 2025. He was found in a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel, the victim of a suspected drug overdose that is currently the subject of an FBI investigation. It was a tragic, lonely end for a man who spent his life chasing the ghosts of similarly tortured geniuses. Now, barely a year later, the camouflage is gone. The family is cutting the locks. The “Louvre of American Cool” (my title, at least) is being crated up for auction at Christie’s in New York City, where it will be sold in a series of high-profile auctions from March 3-17.

I’ve been listening to the tape of our conversation again. It doesn’t sound like an interview anymore. It sounds like a ghost story told by a man who knew the end of the movie before the rest of us did.

I’ve come to view this recording as a historical artifact in its own right, much like the ones he collected, just digital. It is a necessary piece of the puzzle for understanding Irsay and his legacy, so I uploaded it to YouTube. If you’ve ever been as fascinated by him and his collection as I have, I think you’ll find listening to it worthwhile:

The Mount Everest Problem

To understand why Jim Irsay spent $957,000 on Jerry Garcia’s “Tiger” guitar or $2.43 million on Jack Kerouac’s scroll, you have to understand his specific brand of hunger. He collected intensity, not things.

“I think those of us who are insistent about getting to the top of Mount Everest, it’s not because we want to see what’s on top,” he told me, taking a drag of a cigarette. “We wanna get on Everest and say, ‘So now where can we go from here?’ It’s never-ending.”

He compared this hunger to the self-destructive streak in his favorite writers. “It’s this insatiable appetite that it’s never enough. It’s never enough because the only thing that is enough is passion. It’s not, ‘Oh, I won’t take a Nobel Prize.’ No, none of that matters. It’s how I feel.”

Jim felt late to that feeling. He belonged to the “younger brother club.” He grew up in the 70s, watching the older kids go to Led Zeppelin shows while he was stuck with responsibility. By his early thirties, he was running an NFL team.

“My dad was pretty cheap, paying me $100,000 a year... it was kind of like until I took over things and kind of righted a sinking ship... because of my dad’s alcoholism.”

That’s the texture you don’t get in the obituaries. Jim was a billionaire, certainly, but more importantly, he was the man who spent the first half of his career cleaning up the mess his father left behind. Robert Irsay was a tempest, a man who traded the Rams for the Colts in 1972 like he was swapping baseball cards, then held Baltimore hostage for over a decade until the Mayflower trucks rolled out.

Jim inherited that circus. He inherited the anger of a jilted city, the stigma of a “sinking ship,” and the genetic lottery of addiction that had plagued his old man. He inherited a ghost alongside a football team. And while he eventually exorcised those demons on the field—hiring general manager Bill Polian, drafting Peyton Manning, and bringing the Lombardi Trophy to Indianapolis in the rain in 2007—he spent his life fighting the ones in his own blood.

The Truth (And Jack Nicholson)

Once the Colts’ balance sheet finally allowed it, Jim skipped the souvenir hunt and went straight for the raw, high-voltage current he’d been chasing since the beginning. He told me about the moment he realized words could hit as hard as a drum kit. “Before, I didn’t think without Led Zeppelin, John Bonham, and a Les Paul guitar and Marshall Amps that you could have that kind of power,” he said. “But then, when I started reading Dylan Thomas, I was just floored. Floored, floored.”

Jim was obsessed with what he called the “unvarnished truth.” He hated the fake, plastic world of the 1950s that the Beat Generation blew up. He wanted the grit.

“It’s like Jack Nicholson says in A Few Good Men,” Jim told me, revving up for a cinematic deep dive. “’You want the truth? You can’t handle the truth!’”

He paused, letting the line hang there, then pivoted into the sort of cosmic existentialism you don’t hear on ESPN. “The truth is just the truth. It’s like God. You can say, you know, let’s talk about Buddha, let’s talk about Jesus, let’s talk about God. It really doesn’t matter. God doesn’t care what you think, how you worship. God has no interest in that. God ultimately is love and truth.”

For Jim, the artifacts were just vessels for that truth. He bought the Kerouac scroll because it was the physical embodiment of that mania. He bought Jerry Garcia’s “Tiger” guitar at a record-breaking auction in 2002, dropping $957,000 to secure the instrument Jerry played for the last 15 years of his life. He told me, “Small details are huge details. When you see Jerry Garcia on the 24th fret of Tiger put there by Doug Irwin, that’s huge. That’s humongous.”

When I was in San Francisco to see the collection in the flesh, I spoke with Larry Hall, the man Jim hired as the ‘Vice President of Historical Affairs.’ It’s a title that usually exists at the Smithsonian, not an NFL front office. Larry told me that Jim operated with a rigid, almost spiritual algorithm for acquisition. He ignored dusty antiques with modest historical footnotes. He didn’t want the backup guitar. He wanted the battering rams. He wanted the specific tools that artists used to dismantle the status quo. If a book, artifact, or instrument hadn’t shifted the axis of the earth, Jim Irsay didn’t want the receipt.

He lacked the gatekeeping instincts of a purist. He was honest about his own counter-culture credentials. “I wasn’t a Deadhead,” he admitted to me, laughing. “My acid trips seemed to be tied more to Pink Floyd than the Grateful Dead.”

The Gypsy with the Scarf

Despite the Pink Floyd preference, he worshipped the idea of the Dead. “The girl I want to fall in love with isn’t the Prom Queen,” Jim told me, his voice dropping into a reverent whisper. “It’s that gypsy with the scarf coming through town on that wagon pulled by a horse.”

He chased that gypsy wagon his whole life. And he knew that fame was a hollow fuel. “Take someone like John Belushi,” he said. “He was one of the biggest stars 40 years ago, now no one knows who the fuck he is. But that’s just fame... The Grateful Dead is way bigger than the Grateful Dead itself.”

He wanted to tap into that “bigger” thing. It’s why he was friends with Hunter S. Thompson. Jim gleefully recounted a letter Hunter wrote him, scrawled in the margins of Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, where the great doctor called him a “gold bag digging cocksucker.”

“He just goes on and on,” Jim laughed on our call, recounting the insult like it was a Medal of Honor. “’They won’t watch it in Cleveland, and they won’t watch you in Los Angeles... You’ll die in the filth of your greed.’”

James. Hunter called him James. And Jim loved it. He loved it because Hunter ignored the billions; he cared about the frequency.

The Hearse and the U-Haul

We live in a culture of accumulation. We are taught to stack bricks until we build a fortress that death can’t penetrate. Jim had a bigger fortress than almost anyone, and he spent his entire life trying to tear down the walls.

There is, of course, an undeniable friction to this level of accumulation.

I texted my buddy Jason about this while thinking through how to tell this story. He noted, astutely, there’s a heavy subtext to a billionaire buying up pop culture: You bought a guitar with money that could’ve run a homeless shelter for years. It highlights the uncomfortable reality of finite resources flowing upward. In his complexity, it’s like Jim understood the absurdity of it all.

About twenty minutes into our talk, Jim dropped the line that answered that exact question—a phrase that has been rattling around my skull ever since.

“First of all,” he said, waving away the title of ‘owner’ like a bad smell, “No one owns anything. We borrow everything. I’ve never seen a hearse pull a U-Haul.”

He apparently said that line a lot. Not to sound so fatalistic, but I think it’s an awfully good mantra, especially coming from a billionaire with such astronomical means beyond most of our comprehension.

Jim understood stewardship. He declined a $1 billion offer to move the collection to Dubai because he wanted it here, in America, accessible to the people. He believed these objects were alive when played. He refused to let the artifacts rot in a vault. He wanted them to sweat. He threw massive, free exhibitions in cities across America. He’d fly in his house band, let his players strap on the guitars, and belt out Warren Zevon covers with the earnest, gravelly enthusiasm of a billionaire living out his rockstar fantasy. He invited the “looky-loos,” the regular folks who couldn’t afford a ticket to a Colts game, to come in, see the history, and watch the show for free.

My buddy Jason pointed out how oddly timely Jim’s museum project is when viewed through the lens of late-stage capitalism. There’s a relatable fatalism to collecting, especially when it comes to the nearly unlimited resources that an NFL owner has at his disposal—a fuck it, I could, so I did mentality that feels rooted in the current zeitgeist. As Jason put it, everyone is chasing scarcity in a world that feels increasingly hollow. He referenced how someone might work hard at a dead-end job and put half their paycheck on a rare Pokémon card they’ll treasure and keep forever. Irsay, you see, just did the exact same thing on a Jerry Garcia guitar. It’s the universal human impulse to hold onto something that we feel connects us to these parts of ourselves that others might not understand, just scaled up by a few commas.

Because inevitably, all of this circles back to the existential dread of ownership. Jason joked about an extremely rare Mr. Bungle vinyl he cherishes, asking the ultimate collector’s question: Who would I even leave this to? Thanks for making me think about my mortality, dude. I felt that. I look at my own modest stash: a few treasured Phish posters, some Michael Jordan cards from the ’90s still at my parents’ house, my grandfather’s threadbare Penn State sweatshirt, and a promotional Frank Zappa album sent to a Rolling Stone critic in 1972. I realize their heaviest weight is knowing their true value exists entirely in my own head.

But if buying a dirt bike, a Pokémon card, or a Frank Zappa album is renting a chapter, Jim Irsay was trying to buy the whole damn library.

The Torch and the Tragedy

Toward the end of our call, the handlers started circling. Time was up. But Jim wanted to stay. He was revved up. I steered the conversation toward the horizon, asking what the endgame was for a collection of this magnitude. I didn’t know it then, but I was asking the question that would eventually frame the collection’s final act.

“It’s so important for people in their 30s and 20s... to really carry it forward,” he told me. “Because it’s like, more and more we’re losing people... This generation is disappearing quickly.”

He paused, then drifted into a story that hits differently now: a premonition wrapped in an anecdote. “Christie McVie just died,” he said. “And you know, as ironic, I got John McVie’s bass... and like Christie died the next day. It was like, what? This generation is disappearing quickly.”

He didn’t know how right he was.

Jim’s stated goal was explicit: he wanted the collection to last “for the next 100 years plus.” He wanted a permanent museum. Instead, the catalog is being printed. David Gilmour’s “Black Strat” and Ali’s belt are headed for the hammer, perhaps destined for tech CEO vaults and Geneva tax havens, scattered to the wind like ashes. Jim Irsay was complicated—a colorful suit-and-tie mess of billionaire privilege and beatnik soul. But… aren’t we all? He just happened to have a bank account that made his internal contradictions visible to the world.

In that vulnerability, he understood the fundamental assignment of being alive: that we are here to be real, not polished. He quoted Jack Nicholson and Dylan Thomas in the same breath. He name-dropped being friends with Cameron Crowe and helping him on Jerry Maguire. He told me how Peter Berg once told him he likes to write in the morning, when “the fields are rich with writing.” Maybe I’m reading into it too much for a casual interview, but I suspect he wanted me to find those fields, too.

“So I just love all the stuff that you’ve been involved with that’s been great at your age, that you’ve been able to connect up already with people like Anita and do the stuff you’ve done,” he told me.

When I listen to that again, I’m nothing short of humbled that a man like Mr. Irsay said that to me. I’ll cherish that one forever.

If I’m being honest, his encouragement is the reason I still hold onto a stubborn, moonshot dream of one day writing the authorized book or directing a documentary about his collection and its legacy… especially with the new chapter that’s about to unfold in New York come March. Call it manifestation or stating one’s intentions, but sometimes you just have to put these things out into the universe and see if the ghosts answer back. Don’t let your dreams be dreams, you know?

The world will remember the guitars and the football team, but after he died, the real eulogies were more understated. They were stories of a billionaire who made it his personal “ministry” to hand out wads of $100 bills to strangers on the street, or the hundreds of funerals he paid for anonymously, insisting that no one know where the money came from. Most people in his tax bracket look right through you; Jim looked right at you. He didn’t just buy the holy relics of the 20th century; he tried to be a holy relic himself—a flawed, generous, restless force of nature who saw the person behind the lack of pedigree.

He flipped the script and started digging into my own story with a curiosity I still find hard to believe. I can’t say that I have anything in common with an NFL player, or especially an NFL owner, but he recognized a shared frequency through our mutual love of what those artifacts symbolized. He offered a rare kind of validation, an acknowledgment that for 40 minutes, we were just two storytellers chasing the same ghosts.

The tragedy goes deeper than the sale of the items. The tragedy is that Jim was right. The “filth of greed,” as he said, quoting Hunter, usually wins. The U-Haul doesn’t follow the hearse, but the auctioneers sure as hell do.

I’m glad I failed his CIA test, because it let me pass the real one. He pulled back the curtain on the billionaire costume that most people never get to see and showed me a man who knew the machinery was an illusion, like Oz behind the curtain, but the magic of it all was non-negotiable.

Rest in peace, Jim. I hope you found that gypsy wagon. I hope you’re sitting in a farmhouse somewhere with Hunter, Jerry, and Mohammed Ali, listening to the ghosts, realizing that you finally, truly, don’t own a damn thing.

And I bet it feels like freedom.

Brandon Wenerd is the publisher of BroBible.com. He can be reached at brandon@brobible.com

Hell of a post. Thank you!