Mourning the Mischief Makers

Bob Weir found his "azimuth" in the invisible space between the band and the crowd. On mourning the last of the wild American originals, and celebrating their mischief in a very flat culture.

There is a specific kind of spiritual grounding that only happens on a Saturday night at the edge of the continent.

I spent my One More Saturday Night in Redondo Beach, down at the pier, sitting at Quality Seafoods. It was a date night reward for a very busy week living out of a suitcase that took me from a conference in Vegas to the slopes of Mammoth Lakes. It was a very fun and productive week, and I got to hang out with some really cool people! (I actually wrote about that trip over on BroBible; go check out this week’s recently revitalized Things We Want column for the full story).

Quality Seafoods is a great if you know, you know, L.A. spot. It’s not a white tablecloth seafood-tower kind of place; it’s butcher paper and wooden mallets. Since it’s in season, I put down two Dungeness crabs, two ears of corn, and a bowl of clam chowder. It was visceral, delicious, and hard-earned with little nicks on your fingers from picking the shells. I enjoy working for my food, and this was the kind of meal that makes you grateful to be sitting upright and taking in oxygen.

(A quick controversial sidebar for my East Coast friends: I enjoyed the Dungeness, but I’m going on the record—Maryland Blue Crab is still king. The meat is sweeter, firmer, and you have to work a little harder for it. But I digress.)

I came home full of salt air and crab meat, settled in, and turned on YouTube to watch the Bob Weir Celebration of Life.

I wasn’t prepared for how hard it would hit.

There is something disarming about seeing giants being vulnerable. I lost it when John Mayer and Mickey Hart spoke. I lost it again when Weir’s daughters—Monet, Chloe, and Natasha—took the stage to eulogize their late father. And, of course, during “Ripple.” By the time Mayer came out with a guitar to lead the congregation, I was bawling my eyes out.

There is a line that crossed my mind while watching the tribute, and it’s become my new metric for a life well-lived: We should all aspire to live our lives so that we go out to a crowd of people who love us singing “Ripple.” I can’t think of anything more beautiful.

But as I sat there, wiping my eyes and listening to those chords that have been the soundtrack to millions of road trips and late nights and the final scene in Judd Apatow’s “Freaks And Geeks” when Lindsey Weir gets on the bus to go on Dead tour, I realized I wasn’t just emotional about the man or the music. I was mourning something else.

I think part of the collective grief we are seeing right now is the realization that we are losing the Wild American Originals.

I’m talking about the cross-generational architects of mischief. The Bob Weirs, the Nina Simones, the Anthony Bourdains, the Richard Pryors, the Nora Ephrons, the Jimmy Buffetts, the Miles Davises, the George Plimptons, the Bill Waltons, the Hunter S. Thompsons.

They’re gone. And as time marches on, we are confronted with a legacy that is both immortal and painfully finite. Yes, the work is eternal, but the lens is gone. We will never again hear what they have to say about the now. We lose the specific comfort of their reaction to the present, the way they would have metabolized this moment and returned it to us as art.

These were artists who built worlds instead of making content as a means to an end. They were outlaws, but they were our outlaws. They managed to create enduring art that spanned decades, welcoming in new generations without ever polishing off their own rough edges.

Mickey Hart shared a story during Weir’s celebration that perfectly captures this specific frequency of lunatic joy. It was about a full moon in San Francisco, possibly when they were living together in that purple Victorian at 710 Ashbury Street:

“One day we wake up, Bob announced that we were going to the zoo to record the animals. No, it was a full moon, which was very important to Bob. He assured me that’s when the animals are at their loudest... We thought Owsley might loan us his Nagra recorder. So, we showed up and he taught us how to record. Then, at midnight, we arrived at the zoo. But as we climbed the gate, we got entangled in the bike lines. We hung there from the wires on the inside of the fence and laughed so hard that the guards came, shining their lights, grabbing us down. Now, not knowing what to do with us, they let us go. As we left, we paused for a moment and looked back... stopping to consider what the recording might have been. But we found the zoo was totally silent, not a sound. That was perfect, Bob.”

While every generation produces incredible talent, I have a nagging worry that we might not see that kind of spirit again, and that the lore and interpersonal connection eventually manifest as tremendous artistic chemistry. Not because the talent and originality aren’t there, but because the world has shaken out differently around us. And honestly, I think a lot of us who romanticized that old world—where artists brought us comfort simply by flipping off The System—don’t quite know what to make of the new one. I hate to sound so curmudgeonly, but I know I don’t.

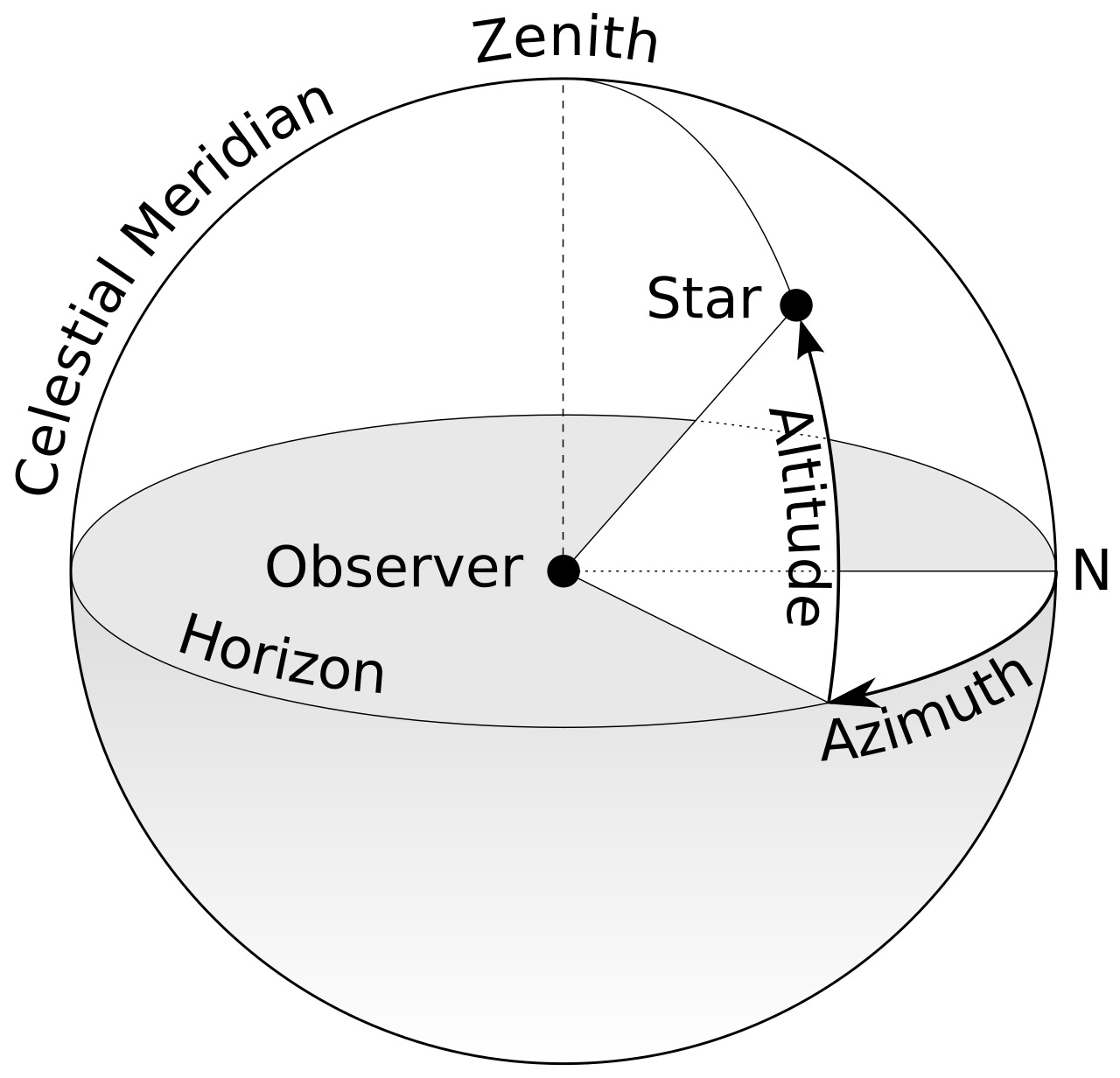

Chloe Weir touched on the mechanics of that relationship during her remarks, recalling how her father explained the unique alchemy of a Dead show. He told her: “We have a kind of special relationship with our fans. What happens is they give us energy. We kind of focus it. We shape it and give it back to them. All this happens right up there. What I’ll call... the azimuth. It’s between us and the audience and the music happens there. They’re as much a part of it as we are.”

She noted that “azimuth” is a navigational term, describing a bearing relative to true north. The geometry-heads out there might recall that it is the horizontal angle measured between that fixed reference point and a celestial object, or the precise geometry of locating oneself among the stars. It’s been used by sailors to roam the earth’s oceans for millennia.

For Bobby, true north as an artist was in that invisible space between the player and the listener. It wasn’t just walking out on stage and collecting a check. That connection was so vital that he admitted it was why they never made great studio records—”cuz [the fans] weren’t there in the studio with us.”

Compare that to today, where the mechanics of devotion have changed. For the tribes that followed Weir or Buffett, fandom was a contact sport. It was physical. You showed up, you got in the van, you shared the space. Today, fandom feels more like a tentpole event for identity curation; less about the shared experience of a come-as-you-are crowd and more about how the artist fits into the curated, engagement-minded aesthetic of our digital lives.

It’s a stark contrast to the modern moment. We live in an era of suffocating “main character energy” and a strange, pervasive monoculture, yet everything feels inextricably fragmented. We are increasingly united not by what we love, but by what we hate—our politics, our tribal grievances, our chosen enemies (whether it’s ICE or the “woke mob”). Monet Weir touched on this, quoting her dad’s refusal to demonize the other side, recalling how he would refer even to “our friends, the Repubs.” He understood that the music was a bridge, not a bunker. Today, we build bunkers. And that dynamic likely isn’t going to shift until we stop waiting for permission to be decent and remember that the Golden Rule is the ultimate form of mischief: treating people with humanity even when a system tells you they are the enemy.

Fandom of pretty much anything these days feels corporate, in a bland and icky way. “Community” is no longer a shared vibration or an “azimuth”; it’s a buzzword lauded by digital gurus and LinkedIn thought leaders—an ethos that is often far more beneficial to the system at the top than the members actually living in it. We aren’t really an “audience” in the spiritual sense anymore; we’ve been reduced to a customer base. And like any good corporation, the modern artist knows that the safest way to retain a customer is to never challenge them, never surprise them, and never risk the brand.

There are exceptions, of course, but culture feels dangerously flat. It has never been easier to consume “content,” yet never harder to find new, wildly transformative art that we want to share with everyone we know. Distribution is a fragmented, algorithmic mess, and making a living has become a dark art of appeasing algorithmic gatekeepers just to unlock a sliver of attention.

We are living in the era of hyper-optimization. The message, the delivery, and the community have been sanitized for mass consumption. To be a “wild child” today isn’t romantic; it’s a liability. To be a “mischief maker” is a PR crisis waiting to happen. The algorithms don’t favor the long, strange trip; they favor the viral spike, the safe bet, the self-help platitudes, the grindset navel-gazing (& gaslighting), and the artist whose wildest ambition is a branded bar on Broadway in Nashville, where one week’s top-line gross revenue might outpace streaming revenue to the actual music for a year. We have traded away the outlaw for the asset.

We still have outlaws, sure. But it’s a different kind of defiance now. It feels more niche, less commercially viable, less central to how the American story unravels itself. The era that allowed a guy like Bobby Weir to come of age, settle into his voice to write a song like “Estimated Prophet” or “Hell In A Bucket” or “Throwing Stones”, wear bolo ties on the stage, play guitar like Bill Evans, and accidentally build a tribe that spans the globe seems to be closing.

So, when we watch these tributes and jot down our memories about how an artist like Bobby Weir fundamentally warped our perspective and changed our own life’s trajectory, we aren’t just saying goodbye to a person. We are mourning the closing of a frontier. We are missing the wildness. The world you grew up in no longer exists, as the saying goes.

But then I think about the pier, and the crab, and the music, and the people singing “Ripple,” and I remember: the frontier might be closed, but the songs are still here. And the instruction manual they left us is pretty clear.

It tells us to stop looking for the next Bob Weir on the main stage or the Trending tab. You won’t find the spirit there. You have to look for the friction. Look for the art that feels a little unsafe, the voices that haven’t been sanded down for mass appeal. Look for people building real-life communities that aren’t easily quantified, where it actually matters, and not just follower counts.

There is a road, no simple highway… Between the dawn and the dark of night… And if you go, no one may follow… That path is for your steps alone.

The path is for your steps alone, but the music, even if it’s not music, is for everyone.

So go find the ones walking their own road. Support the messy, the weird, and the wild.

Be kind. Make mischief. And live a life worth singing about.

If there’s one or two current artists with the outlaw spirit , I’d point to Jesse Welles and King Gizzard